Let’s talk about a scary, yet very important word in the educational world: feedback. Yes, I referred to feedback as scary – want to know why? As educators, we wonder how to provide feedback to our students often. What is the right approach in terms of delivering the feedback? What is too much feedback? How specific should we get? The questions are endless, but the topic is one that is incredibly crucial and necessary towards helping students to grow. But, why? Why is it necessary to continuously provide feedback to our students?

When I go to the gym, there is an individual there coaching us along the way. One day, as I was working on a particular workout, the coach came over and said, “I like the heaviness of the weight you chose. Now, let’s focus on not jumping too much. Try this…” She proceeded to show me how to execute the workout again, then stayed around for another 30 seconds to ensure I picked up on it correctly. Why was this so important? First, she applauded me for something, which made me feel good and reminded me the next time we performed that workout to stick with the weight [even though it was really challenging]. After that, she corrected my form. This was especially crucial in order to prevent injury. Finally, she stayed around while I performed the workout again in order to ensure I applied her feedback correctly to avoid getting hurt. Not one time did I feel embarrassed while she was providing me the feedback during class. This didn’t only help me do better for the rest of that specific class, but it helped me to improve in following classes.

Feedback to our students is important in aiding to their academic improvements. Whether it is written, oral, or recorded – it is a necessary part of education. How will our students know when they are making a mistake, and what will help them to improve? But, as with many things, there are barriers to the feedback that is provided to our students (especially as they get older). Take this for example: you spend hours correcting those essays and writing feedback throughout each one to help your students understand where they did great and where they struggled. You are proud of that feedback, and know that it will help them to grow. You add the grade at the top, or on the rubric. You hand those essays back to the students and the majority immediately look at one thing – the grade. They focus on the grade (this topic is for another day…), but don’t spend much time paying attention to the feedback. Often times once this happens, we move on to the next topic.

Feedback must be purposeful and meaningful. I’ll say it again – FEEDBACK MUST BE PURPOSEFUL AND MEANINGFUL. It must inform our instruction. If nothing is being done with the feedback, then you, as an educator, just wasted a whole bunch of extremely valuable time writing meaningless words on a piece of paper. So what do we do? How do we overcome this? I don’t have all of the answers, but I do have a few ideas!

Give them a day!

When I taught in a setting where I was giving quizzes and tests, I would always build in time (sometimes a full class period…) allowing students to work on corrections. We did this together because I knew that my middle school students needed guidance and support with how to do this in a way that was beneficial. As a matter of fact, the first few times we did this I modeled how to do it using a made-up assessment. I walked

my students through the process. I told them to never forget about the ones they got correct, that those show us our strengths. We discussed the importance of looking at problems that we got correct, but remember feeling nervous about while taking the assessment. Then, we focused on the mistakes we made. We discussed the importance of reading the feedback. I would copy a problem from the test for students to see and we had in-depth conversations about what the feedback meant for that problem, and how we would use the feedback to correct our understanding. Once the students got the hang of this, we would spend half or a full class day working on corrections. Not only did this help improve their grade, but it also helped to improve their overall understanding, preparing them to move on to the next topic.

Use the same homework for many days in a row

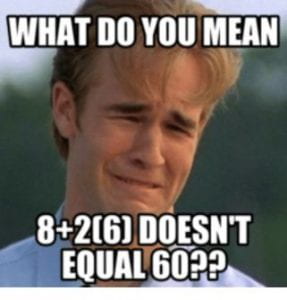

As a math teacher, I thought that it was important for my students to complete a lot of problems for homework because practice makes perfect. After many self-reflections, I realized the importance of quality over quantity. What does assigning a ton of homework (or homework, at all – yes, I said it) do for many of our students? Well, some won’t do it at all because it’s just too much and overwhelming. Some will cheat because they didn’t have the time to finish and they don’t want to see a zero on their progress report. Some will take the time to work on it. These are just a few scenarios out of many. But, even if they do take time to work on the assignment, what good will it do if all we do the next day is quickly go over the answers (like I used to do)? You know what I am talking about:

“Okay, so we just finished going over the twelve questions from homework. Does anyone have any questions or need me to repeat any answers?” [Crickets. Not one word] “Great, then let’s move on to the next topic.”

You know there are definitely students out there who are still struggling after that assignment, but just may be too embarrassed to say anything. Now let’s reflect – how did this assignment help us to improve? Did we provide specific feedback to any students, or did we just check for completion and move on? Feedback on homework is just as important as feedback on assessments. If you are going to have your students complete an assignment, just to show you that it is done and listen to you recite the answers, then that homework is not meaningful. If you are going to assign homework, provide students with an opportunity to grow with that assignment. If I were still assigning homework, I would have started with assigning my students a few – maybe two or three – problems on one night. The next day I would give my students the answers (yes, I said it – I would just give them the answers). I wouldn’t spend time reviewing at that point. The homework for tonight would be to take those problems and redo any incorrect questions. Got them all correct? Great! You’ve mastered that topic. Here are a few optional and/or challenging questions if you’re wanting to do more with this. They come back the second day and some still got wrong answers. What do we do from here? We create a small group, provide feedback on the questions, and help the students to understand better. Does this require a bit of time management? Yes. However, I would rather try to find a way to make this work than go over homework everyday when I know my students aren’t going to ask questions because they don’t want to hear me talking about it anymore (you know I’m right!).

Provide VERBAL feedback – digitally!

Since the pandemic and beginning remote learning, many of us have been assigning activities/assessments on a digital platform. There are many tools out there that can allow you to provide verbal feedback to students digitally. Grading something on Google Docs? Open up a Screencastify and talk your feedback as you are grading the assignment. Did you just finish grading a project that was turned in? Open up FlipGrid and allow your student to watch you point to their project as you are speaking and providing feedback. Not only will this be done quicker than hand-writing all of the feedback, but it will also allow your students to build more of a connection with you as they are watching and/or hearing you provide feedback and explain.

These are only a few suggestions on how to provide meaningful and purposeful feedback to students. Remember, feedback is meant to help them grow and improve; but only if we are providing them a way to do something with the feedback. Taking it one step further and using what we provided to inform our instruction is what will really aid in their overall understanding. Please feel free to share in the comments with ways you allow students to grow from the feedback you provide them with!

you want the students to stand when tossing the ping pong ball.

you want the students to stand when tossing the ping pong ball.